09 June

Bible In 365 Days

Job 29-31

Job 29

Job now moved a step forward in his reply. He was still without a solution. That of his friends he utterly repudiated. In order to prepare the way for the utterance of a solemn oath of innocence, he first looked back at old and lost days in order to compare them with his present condition.

In this chapter we have his description of the past. It is introduced with a sigh:

"Oh that I were as in the months of old."

That condition is described first in its relation to God. They were days of fellowship in which Job was conscious of the divine watchfulness and guidance. Then in one sentence which has in it the sob of a great agony, he remembered his children:

"My children were about me."

He next referred to the abounding prosperity, and, finally, to the esteem in which he was held by all classes of men, even to the highest. The secret of that esteem is then declared to have been his attitude toward men. He was the friend of all who were in need. Clothed in righteousness, and crowned with justice, he administered the affairs of men so as to punish the oppressor and relieve the oppressed. He then described his consciousness in those days. It was a sense of safety and strength. Finally, he returned to a contemplation of the dignity of his position when men listened to him and waited on him, and he was as a king among them.

Job 30

Immediately Job passed to the description of his present condition, which is all the more startling as it stands in contrast with what he had said concerning the past. He first described the base who now held him in contempt. In the old days the highest reverenced him. Now the very lowest and basest held him in derision,

"Now I am become their song.

They chase mine honour as the wind.

But yesterday the word of Caesar might

Have stood against the world; now lies he there,

And none so poor to do him reverence."

So Shakespeare makes Mark Antony speak over the dead body of Cesar. In the case of Job the experience was more bitter, for not only did the poor refuse to reverence him, the base despised him, and he had not found refuge in the silence of death. In the midst of this reviling of the crowd, his actual physical pain is graphically described, and the supreme sorrow of all was that when he cried to God there was no answer, but continuity of diction. He claimed that his sufferings were justification for his complaint. All this precedes the oath of innocence. Before passing to that, it may be well briefly to review the process of these final addresses. Job first protested his innocence. Then he poured out his wrath on his enemies. Following this, he declared man's inability to find wisdom. Finally, he contrasted his past with his present.

Job 31

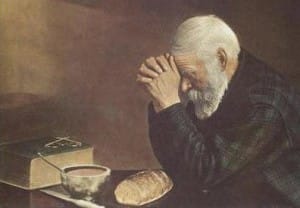

This whole chapter is taken up with Job's solemn oath of innocence. It is ills official answer to the line of argument adopted by his three friends. In the process of his declaration he called on God to vindicate him. In the next place he asserted his innocence in his relation to his fellow men. As to his servants, recognizing their equality with him in the sight of God, he had not despised their cause when they had contention with him. Toward the poor he had acted the part not only of justice, but of benevolence. He had not eaten his morsel alone. He was perfectly willing to admit that his uprightness had been born of his fear of God, but it remained a fact.

Finally, he protested his uprightness in his relation with God. There had been no idolatry. His wealth had never been his confidence, neither had he been seduced into the worship of nature, even at its highest-the shining of the sun and the brightness of the moon. Moreover, he had no evil disposition to cause him to rejoice over the sufferings of others, and in this there would seem to be a satirical reference to his friends. Finally, in this connection he denied hypocrisy.

In the midst of this proclamation of integrity he broke off and finally cried, "Oh that I had one to hear me!"

In parenthesis he declared that he subscribed his signature or mark to his oath, and asked that God should answer him.

The final words, "The words of Job are ended," are generally attributed to the author of the book, or some subsequent editor, or copyist. I cannot see why they do not constitute Job's own last sentence. He had nothing more to say. The mystery was unsolved, and he relapsed into silence, and announced his decision so to do.