24 May

Bible In 365 Days

Nehemiah 1-3

Nehemiah 1

This is the last Book of Old Testament history. An interval of about twelve years occurred between the reformation under Ezra and the coming of Nehemiah. The story is the continuation of the work commenced by Zerubbabel rebuilding the wall.

With a fine touch of natural and unconscious humility, Nehemiah tells us, in parenthesis only, what his office was at the court of the Gentile king. He was cupbearer. Such a position was one of honor, and admitted the holder not only into the presence of the king, but into relationships of some familiarity. Nehemiah's account of himself in this chapter gives us a splendid illustration of patriotism on the highest level. It is evident, first, that he had no inclination to disown his own people, for he spoke of those who came to the court as "my brethren." In the next place, it is manifest that his consciousness of relationship was a living one, in that he held intercourse with them. Moreover, he was truly interested, and made inquiry concerning Jerusalem.

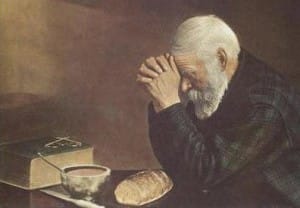

The news brought to him was full of sadness, and all the man's devotion to his people was manifest in his grief as he heard the sad story. The final proof of true patriotism lay in his recognition of the relationship between his people and God, and in his carrying the burden of God in prayer. The prayer itself was full of beauty, and revealed a correct conception of what prayer under such circumstances ought to be. It opened with confession. Without reserve, he acknowledged the sin of the people, and identified himself with it. He then proceeded to plead the promises of God made to them, and ended with a personal and definite petition that God would give him favor in the eyes of the king.

Nehemiah 2

Nehemiah's sadness could not wholly be hidden. He had not been habitually a sad man, as he himself declares; but the sorrow of his nation manifested itself as he stood before the king.

It has been suggested that this was part of his plan. Such an interpretation strains the narrative, for Nehemiah confessed that when the king detected signs of mourning he was fled with fear. Yet through fear a splendid courage manifested itself as he told the king the cause of his grief, and boldly asked to be allowed to go up and help his brethren. The secret of the courage that mastered the fear appears in his statement, "I prayed to the God of heaven, and I said to the king."

His prayer being answered, he took his departure for Jerusalem. His sagacity is displayed through all the subsequent story. It appeared first on his way to Jerusalem. He arrived quietly, and not trusting to the reports which had reached him, he made private investigation. Having ascertained the true state of affairs, he gathered the elders together and called them to arise and build. Opposition was displayed at once by surrounding enemies, and with strong determination Nehemiah made it perfectly clear that no co-operation would be permitted with those who derided the effort. It is impossible to read this story without learning how the work of God should be prosecuted under difficult circumstances.

Nehemiah 3

This chapter is supremely interesting in its revelation of method. That it is preserved for us at all shows how system characterized Nehemiah's procedure. The description proceeds round the entire wall of the city. Beginning at the sheep gate near the Temple, through which the sacrifices passed, we pass the fish gate in the merchant quarter, on by the old gate in the ancient part of the city, and come, successively, to the valley gate, the dung gate, the gate of the fountain, the water gate, the horse gate, the east gate, the gate Miphkad, until we arrive again at the sheep gate, where the chapter ends.

It has been said that this is not a complete account. It is far more likely that where difficulties arise in the length of the wall covered by the section, the solution is in the fact that the wall was not everywhere in as bad repair as at some places. The arrangements indicated the necessity for speedy work, and were characterized by a sense of the importance of division of labor, and a fitting apportionment thereof in the matter of persons and neighborhoods.